The two Ogden’s adverts from The Illustrated London News (ILN) featured in the Smoking Gun gallery are departures from their general style of advertisement which up to this point had been determinedly civilian.

Ogden’s first advertising campaign promoted the exotically named Otto de Rose cigarettes (“Deliciously Creamy”) from December 26, 1891. Their style was very traditional, with simple strips of text extending across the width of the bottom of the page, relying on bold lettering to catch the reader’s attention. Two were posted in January 1892 (9 and 23) and one on 20 February. The latter is totally overshadowed by the finely illustrated Elliman’s embrocation advertisement championing its use for man and beast – and further endorsed by England’s strongest woman.

On the 26 March, they adopted a much more eye-catching approach. Seated before a huge blackboard, a smoking artiste with seductively low backed gown and black stockinged legs, reviews her handiwork. The stern injunction BEWARE OF IMITATIONS looms over the advert– a continuing concern throughout subsequent campaigns. Madame l’artiste featured once in April and twice in May, then vanished until 3 September. At this point, she accompanies the headline news that Dr Tassinari’s experiments reveal exposing cholera bacilli to tobacco smoke “had fatal effect on germ life”. An even better reason to take up the habit. Her return was short-lived, and her final outing was in November 1892.

Introducing the Guinea-Gold brand – “an essentially British Ring” (C. Manners-Smith, 1902)

Thereafter Ogden’s used the ILN pages to promote their “Guinea-Gold” brand. They were not the only tobacco manufacturer featured, but from January 11, 1896, their eye-catching, often humorous adverts appear regularly. They experimented with various styles of advertisement, from simple, rather basic images to more sophisticated Punch-style cartoons. A consistent ploy was to feature ‘Ogden’s’ in largest typeface, followed by a smaller, but still prominent, “Guinea-Gold”. When not included in the main copy, brand name and manufacturer appeared on cigarette packets included in the artwork. This was the time of the tobacco wars, and Ogden’s brief ownership by the American Tobacco Company between 1901 and 1902 may have influenced some of their marketing approach, but they appear well set on the road beforehand.

Marketing “gimmicks” or value added?

In June 1896 Frank O’Neill’s rather crudely drawn railway guard offered free insurance in every packet with clarification of the deal appearing on 19 September. Smoker’s – “and who doesn’t puff the cigarette nowadays?” – were urged to try Ogden’s “Guinea-Gold” cigarettes. Done up in neat little packets of 10, including a £100 insurance coupon against railway accidents and “a pretty little photograph of some footlight favourite”. Furthermore, “Every patriot would naturally smoke cigarettes of British manufacture, as Ogden’s are, and the Guinea-gold brand is so good that its increasing sale is not to be wondered at.” The stress on British manufacture, by a British workforce was a recurrent one. The fact that the tobacco being processed was not home grown was conveniently overlooked.

Ogden’s advert of 24 July 1897 detailed a £100 payment to Ellen Lock, widow of Thomas Lock fatally injured in June while cycling. Trains are not mentioned, but the deceased had been carrying one of the coupons. No subsequent mention is made of the scheme.

Collectible cigarette cards – an opportunistic use of what would otherwise have been a plain packet stiffener – are the focus of the 26 December 1896 advert but rarely feature thereafter. The exception is the advert of 14 July 1900 (p.70) launching the series “OUR GENERALS” with “real photographs of all the most celebrated Officers at the Front” in South Africa. By October 6, a series of Real Photographs of prominent (British) politicians were being issued in Guinea-Gold packets. The following year Ogden’s repeatedly advertised a public photographic reproduction service. How far the continued fighting generated such a demand is not clear. A gap in the market had been identified, and Ogden’s certainly had the wherewithal to fill it. Meanwhile, examples of the mounted prints could be viewed in all tobacconists.

The next logical step – collecting coupons to be exchanged for “valuable” presents – surfaced in August 2, 1902. Ogden’s various brands – Tabs, Guinea-Gold and Royal Navy cigarettes; St Julien and Redbreast Flake tobacco; Uncles Toby and Jack Shag, and Coolie Cut and Lucky Star Plug – all carried them. However, to obtain the free Grand Illustrated Catalogue required a penny stamp. This advertisement also seems to mark the end of the Ogden’s/ILN regular relationship.

Countrywide appeal

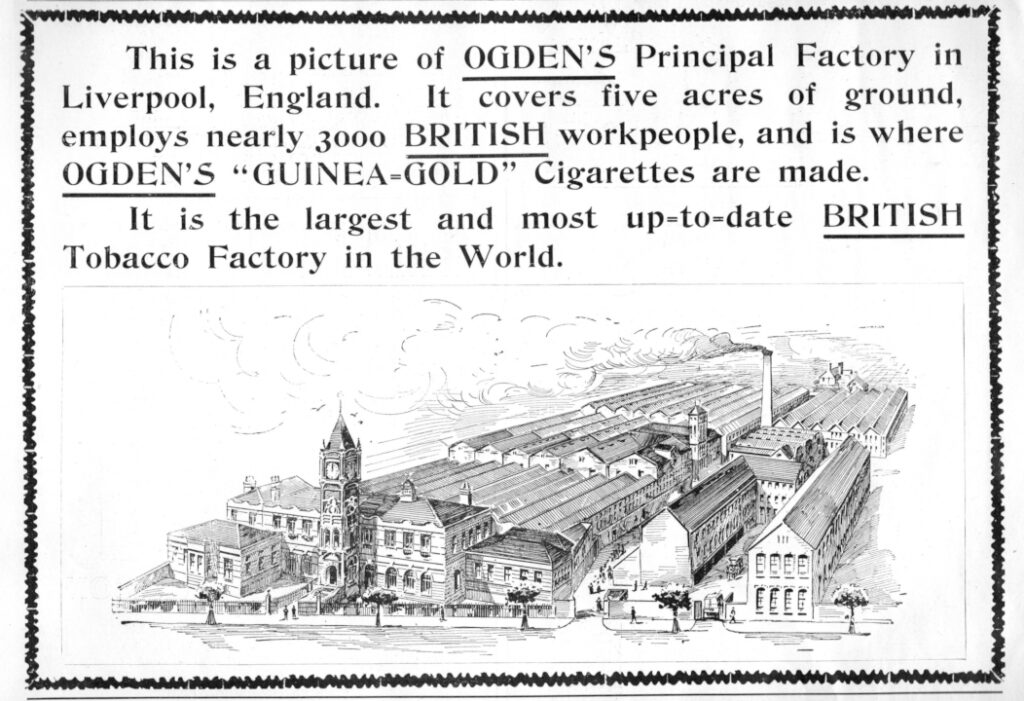

Ogden’s aimed to attract as wide a market as possible and occasionally inserting statistics into adverts – “5,000 miles of Guinea-Gold cigarettes consumed yearly” (11 November 1896); 2,000 rising to 3,000 British staff employed. As production increased, they were keen to emphasize their countrywide popularity extended beyond Liverpool, the home of their main factory. The quality of their product was another stated theme, subliminally reinforced by many of the smoking figures illustrated being drawn from the “better sort”. The housemaid dusting the drawing room in June 1902 guilessly comments “It’s wonderful about these ‘ere Ogden’s “Guinea-Gold”, every new place I go to, the master smokes ‘em”. The periodic inclusion of comic tramps and yokels suggested a more egalitarian demographic but attempts to widen the net beyond white Europeans (June 26 1897 & June 3 1899) were halfhearted and short-lived.

The fairer sex

The tobacco industry offered employment opportunities for women as illustrated in the interior view of the packing line featured in 23 November 1901 (p.802), but they do not appear to have been regarded as prime target consumers. A daring advertisement in 16 September 1897’s ILN (and again 11 December) features a bold lady cyclist, bloomered, and with cigarette between her lips, but generally ladies were merely decorative. They agreed annually from 1897 -1901 (excepting 1899) to gentlemen smoking in railway carriages – providing it was a “Guinea-Gold” – while an 1898 footlight favourite confessed ‘My brother smokes Ogden’s’. However, 9 November 1901’s advert (p.717) puts Eve firmly in her place, with a seated formally dressed couple, complete with background potted palm, her head resting on his shoulder as he smokes captioned “How to be happy though married. The husband smokes OGDEN’s GUINEA-GOLD cigarettes, and the wife thinks them delightful”.

The occasional risqué maverick slipped through – or is that the jaundiced eye of the 21st Century? A 1901 advert (20 April, p.584) voices a sentiment which other manufacturers later adopted as their own. A realistically drawn young couple sit on a riverbank. The gentleman lounges behind his young lady, with only his discarded boater, the smoke from his cigarette and legs visible. She looks out over the river, commenting “You don’t love anything better than one of Ogden’s Guinea-Gold”. His caddish reply? “Oh yes I do. I love two”.

By 24 May 1902, a couple are reclining on the sofa – she is what can only be described as ecstatically smoking, while he sneaks his hand towards her open packet of cigarettes captioned “In love with Ogden’s “Guinea-Gold”. Perhaps the more modern connotation of one occasion to smoke had yet to surface. As for the umbrella concealing the young couple on 20 October 1901 (p.581), with the caption “Give me a little puff – are they Ogden’s?” “RATHER” …

Politics & Jingoism

Ogden’s ILN default style of advertisement relied on simple, eye-catching visuals, bold typefaces and wordplay. However, as early as 2 October 1897, they dabbled a toe in politics. Sir Michael Hicks-Beach’s budget speech quote of 29 April that year, “Our people have smoked more during the last year than ever before” illustrates Ogden’s Guinea-Gold’s success. To 21st century sensibilities it seems an inappropriate statement, posing the question ‘why?’. March 1901’s Chancellor isn’t even named. However, he spawned a topical advert showing a chap on his hearth, piles of you know which cigarette stacked high in the background, smugly declaring “I don’t care what the Chancellor does, I’m all right”.

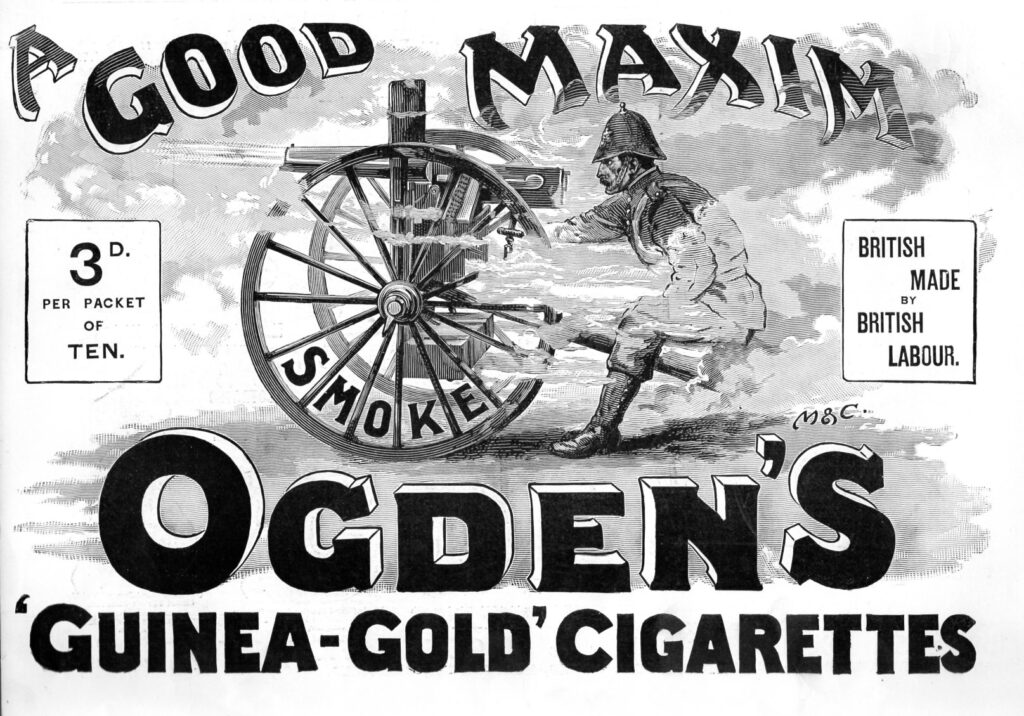

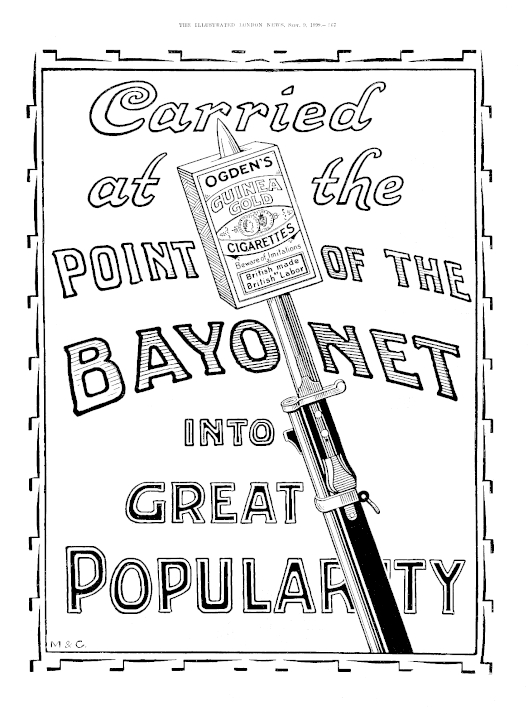

January 13, 1900 (p.60) saw an updated version of the “good Maxim” advert, with Guinea-Gold cigarettes forming the gun, and as the year progressed Ogden’s ILN advertising campaign intensified. Humorous civilian scenes gave way to illustrations reflecting the war in South Africa staunchly supported by Guinea-Gold, many of them echoing the magazine’s photographs of action and military life in the field. Some included political caricatures of the Boer leaders – rather lost on modern readers. By the autumn the home front was taking over again, but on December 29 1900 and January 12 1901 Ogden’s copywriters skillfully used medical science to combine both. Under the banner headline “Important to Smokers” and the established manufacturer/brand logo, the Lancet’s reports on the beneficial use of tobacco by “our soldiers” during the war was pure (Guinea) Gold. “We are inclined to believe that used with due moderation Tobacco is of value second only to food itself” and of course “If tobacco is good for the soldier, it is equally so for the civilian, but see that you smoke pure tobacco”. Carte blanche to light up!

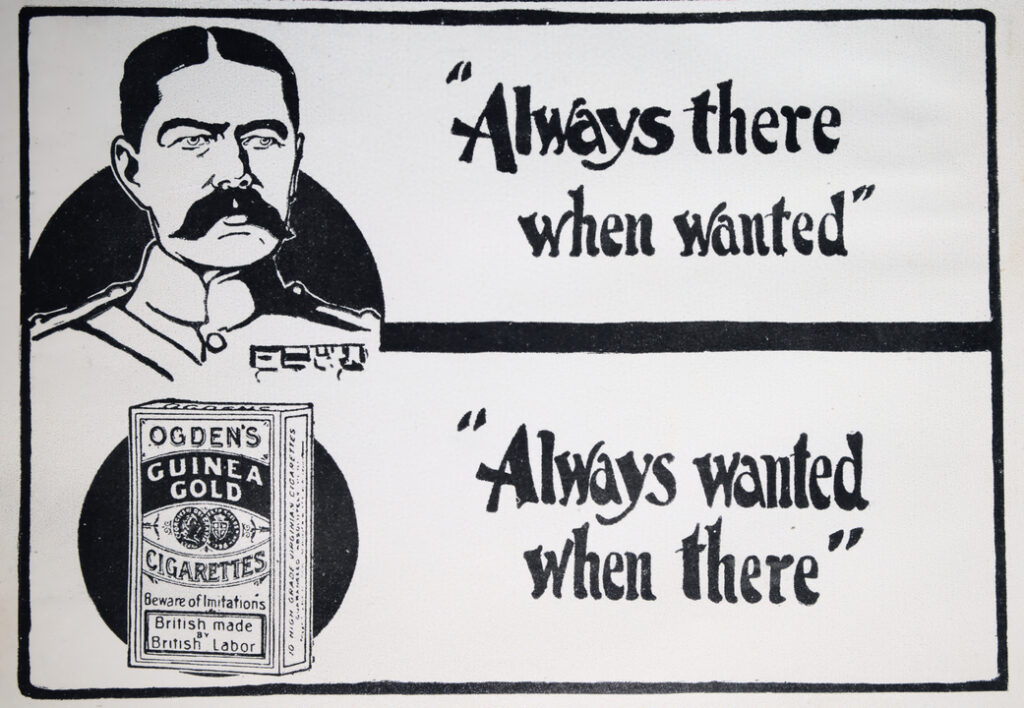

Perhaps the last word from the war is strangely prophetic – armed as we are with the advantage of hindsight. Young Kitchener surveys us, foreshadowing his later famed recruiting poster stance (now de-bunked).

[Kitchener Ad – March 9, 1901, p.359]

The next generation

Perhaps the most shocking of Odgen’s advertisements to the modern eye are the family ones. Obviously intended to be humorous reflections of upper middle-class life, they bring home the complete cultural change in the attitude towards smoking. Cartoon schoolboys sneaking a smoke (Feb 24, p.273; December 8, 1900, p.865) or football kitted youths (29 March 1902, p.469) and the recurring cheeky boy-chimneysweeps aping a toff are one thing – but babies?

The absent-minded father writing at his desk giving the baby next to him a cigarette (26 Jan 1900, p.140; 16 March, 1901, p.140) morphs into a winsome toddler in Papa’s arms lisping “Daddy, me smoke Ogden’s” (18 May 1901 p.719). By 21 June 1902 (p.925) the ringleted poppet stands on a chair to place a cigarette in Papa’s mouth as he prepares for a formal evening out, demanding he shut his eyes and open his mouth. How times change. Perhaps the most bizarre advert actually qualifies for the Smoking Gun theme, appearing on Saturday June 30 1900 (p.887), but I have yet to secure a copy. A skirted young boy (the tradition of dressing aristocratic youngsters of both sexes in skirts until out of the nursery was approaching its last throes), sporting sailor beret sits along a cigarette (guess whose?) protruding from a ship’s gunport with appropriate (?) caption “The Great Gun of the Cigarette World”. It is unfortunate that he looks as if he’s mistakenly wandered over from the Pear’s soap ad.

ILN 4 Jan 1902, p.28; featured Dec 21,1901, Jan 4,18, Feb 1 &15 1902

The 31 May 1902 edition of ILN featured a three page, lavishly illustrated article – 22 photographs in all – on Ogden’s Liverpool factory penned by C Manners -Smith (Cantab). “A British Object Lesson” offered reassurance that the old country still had lessons to teach the world, despite the fears of an “American Invasion”. Outlining the history of the firm’s growth from 1860 when “A cigarette was a thing rarely seen in England, except in the mouth of a foreigner”, crudely handmade, lacking uniformity and produced in less sanitary conditions than 1900’s “perfect cleanliness”. Ogden’s progressive factory “built by British hands, of British materials and controlled by thousands of Britons upon strictly British lines” is lauded by the author. The 3,000 staff of “cheery men and buxom busy Liverpool lasses” are happy and involved, working in “clear north light with absence of glare” ably assisted by “docile” electric power. The cigarette packing machines with their humanoid metal fingers “seem to do everything in keeping with their mission except to think”, producing 575,000 packets a day. Ogden’s marketing department must have purred.

Three months later Ogden’s vanished from the pages of the ILN. On the 16th August 1902, “OGDEN’S BEESWING Golden flaked Cavendish Tobacco manufactured at the International Bonded Tobacco Works, Liverpool” (16 August 1902, p.263) appears their last outing. Ogden’s tobacco is included among others in British American Tobacco Ltd.’s 13 September 1941 advert (p.356) with Duty Free status for British POWS, Sea Going Ships & HM Forces serving overseas. Hardly the prime billing enjoyed in the “Guinea-Gold” years between 1896 and 1902.